10 Mar SUFFRAGETTE CIRCUS

This is a re-post by The Virtuoso. This article originally appeared on The Virtuoso, on March 1st 2016.

Today, a story that has nothing to do with science or literature, but one in honor of Super Tuesday and Women’s History Month: women’s suffrage! Specifically, women’s suffrage in the circus! And no, it’s not about the clowns in the current presidential race. (That comparison is offensive to clowns.)

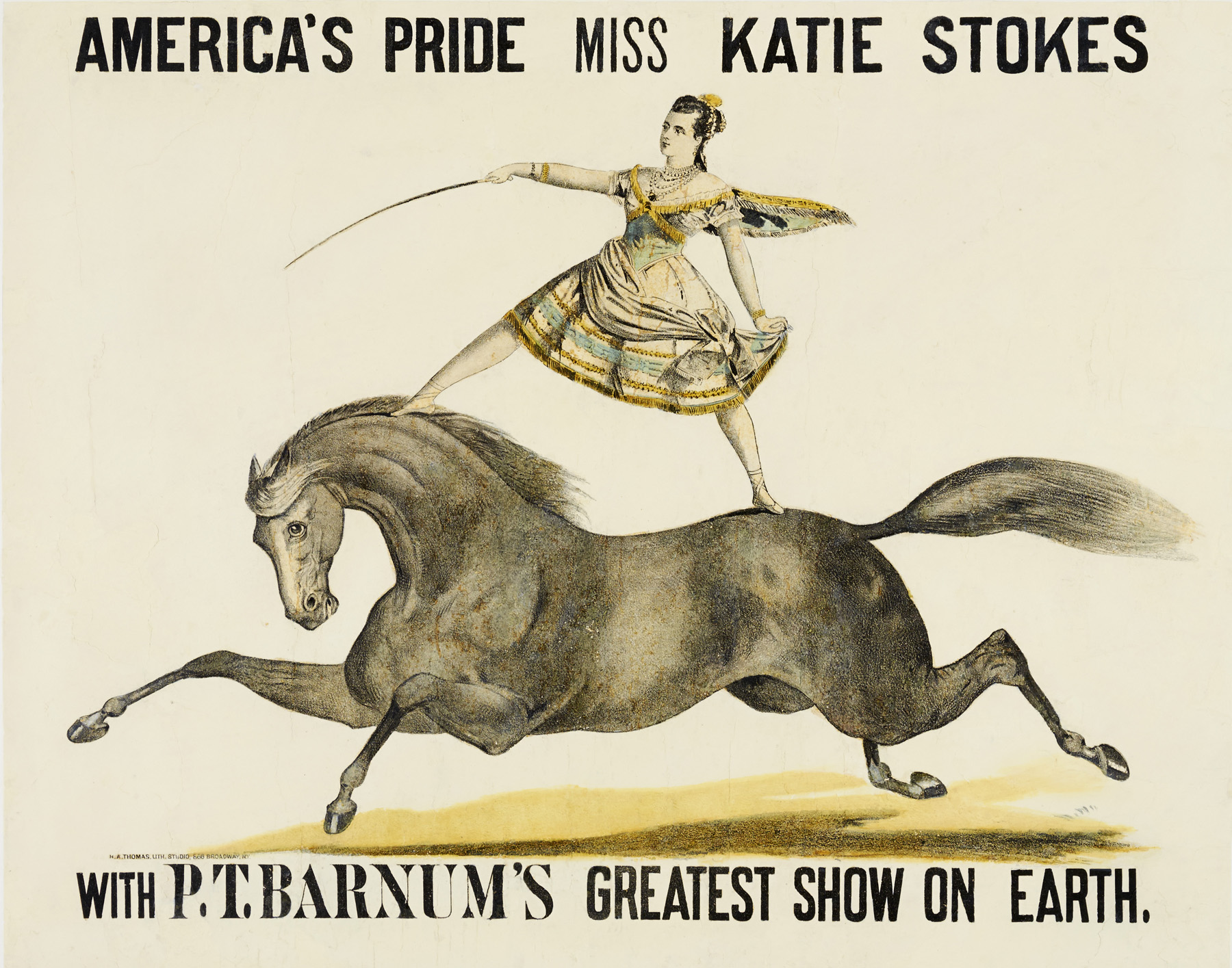

When you think of the circus these days, your first association might be with elephant emancipation. But you also might imagine scenes from the heyday of the Barnum & Bailey Circus, and in the early 20th century, the Greatest Show on Earth was tied up not with animal rights but with women’s rights. Long before the Nineteenth Amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote was passed in 1920, suffrage and the circus had a fraught relationship that was alternately sympathetic and antagonistic. News stories from the 1900s draw a clear line between two camps of suffragettes with the same goal but drastically different methods: the proper ladies, and the three-ring types.

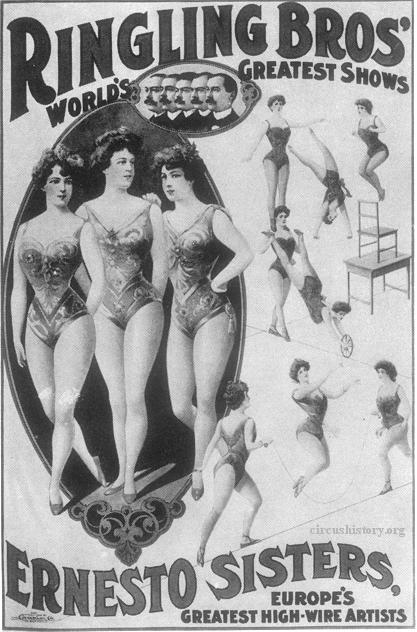

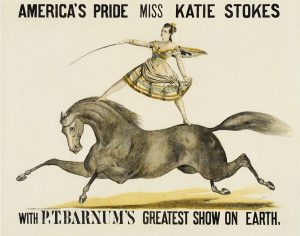

It’s a bit of historical overlap between entertainment and politics that might look obvious. The circus, though marginal in today’s entertainment landscape, used to be the center of social life when it came through town. It featured boisterous actors, animal performances, and, most importantly for suffrage, independent women engaging in solitary and dangerous acts.

[For more awesome posters of circus ladies, see Janet Davis’s post on Circus Now.]

In an arena where a woman could juggle men like bowling pins and drive an automobile in a loop-de-loop, a marriage of suffrage and the circus seems like a convenient and logical one. Many women in the circus earned pay equal to that of their male counterparts and even held the job of ringmaster. Unlike in other fields, in the circus there were few pay discrepancies between men and women likely because there were no discernible physical ones. On the other hand, the circus was a place of contradictions: women engaged in thrill-seeking behaviors that would be unacceptable outside of the ring (“running off to join the circus” to this day is an analogy for wild abandonment of more suitable activities). The taboo nature was part of the attraction for the audience, but it stirred up trouble when suffragists inside the circus tried mixing with those outside of it.

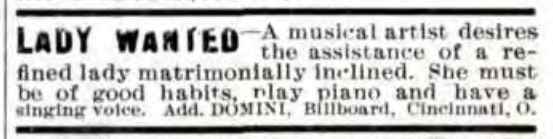

An advertisement in The Billboard from July 1905 solicits “a refined lady matrimonially inclined.” Women in the circus could be wild in the ring but were expected to be proper ladies outside of it.

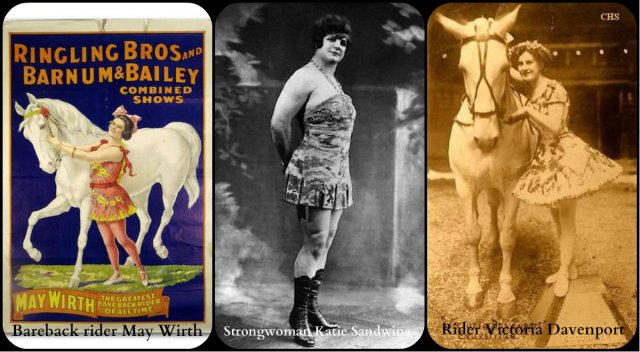

One group of circus suffragettes, led by Josie DeMott Robinson, a retired bareback rider, Zella Florence, an acrobat, and Katie Sandwina, a renowned strongwoman, were particularly active. In 1912, the women called a meeting at Madison Square Garden in New York City to elect officers for their newly created Barnum & Bailey’s Circus Women’s Equal Rights Society—and also to christen a baby giraffe “Miss Suffrage.” Whether they wanted official press coverage or not isn’t clear (maybe they wanted a public photo op along with a private meeting), the press showed up in droves—and, naturally, mocked them. “By nightfall [the giraffe] couldn’t abide even the sight of a suffragette,” snarked the New York Times report of the event, in which the writer refers to suffrage as “proselyting.” “They Organize As Man-Eating Hyena Grins, Elephants Trumpet,” was the actual New York Tribune headline.

Still, they reported the clear words of DeMott, who urged earnestness perhaps surprising considering the reputation of the group: “You earn salaries. Some of you have property. You have a right to say what shall be done with it. You want to establish clearly in the mind of your husband that you are his equal. You are not above him, but his equal. You are not slaves.” Then, reporters found a better hook in an angry husband storming in to reclaim his wife as DeMott spoke. The Sacramento Union reports that during the event of “militants organizing,” it was lucky that a man showed up: “Alexander Sebert, husband of Lillian Sebert, a bareback rider, projected himself into the meeting, took his wife and her sister, Jennie Byram, and hustled them out of the menagerie room in Madison Square Garden, where the meeting was being held. Sebert shouted that he didn’t intend to let his wife take part in such nonsense.” The news in the early 20th century is in fact full of husbands removing their activist wives from such meetings, usually because their dinner has been delayed.

It’s hard to say if the reporters covering these events are particularly condescending, or just the regular amount of condescending for 1912. These kinds of events weren’t hard news, or vital political coverage—they were gossip page fodder. News pieces were given the angle likely to attract the most buzz (not much has changed, obviously—in the Women’s Political Union’s literature I expected to find a listicle of “29 Ways to Jazz Up Your Next Suffrage Event”). On the front page of that same edition of the Sacramento paper is an article about the “venerable” 82-year-old Belva A. Lockwood, who twice ran for president and had turned her attention to suffrage. (That article, in turn, appears directly above an op-ed titled “Girls! Girls! Shame on You! What’s the Matter? Read This – Only 56 Marriage Licenses Granted Last Month, and This Is Leap Year, Too.”) These were not evenhanded treatments of important issues of gender equality. They were clickbait.

Certainly, the public image of the circus’s superficiality was not lost on more socially respectable suffragists. The giraffe incident was supposed to feature Inez Milholland, a prominent member of the New York City-based Women’s Political Union, but she failed to appear, instead sending low-level representative Beatrice Jones to the event to get a sense of what the circus women were like and perhaps ask them to tone it down a bit. The news report does not fail to note this fairly major snub.

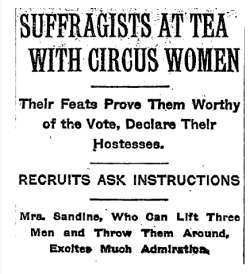

A week later, the Women’s Political Union did host the circus representatives at tea. Evidently they felt more comfortable meeting with acrobats and strongwomen in an interior space, on their terms—and that resulting news article in the Times reads more like a proper society-page story. Not to say it was any more favorable toward suffrage or even represented women as real people. At least as much attention is paid to what kind of hats the women wore as to their views concerning civil rights. (And both are paid more attention than even the spellings of their names: Katie Sandwina is called “Kate Sandine” and May Wirth is rendered as “Mae Worth.”)

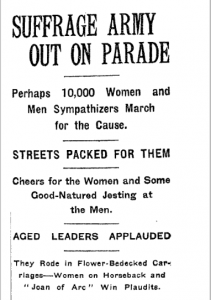

In any case, the women of the circus grappled constantly with a public view of their profession as all flash and no substance, their campaign as a continuation of P.T. Barnum’s famous hoaxes. A Timesarticle about a pro-suffrage parade only weeks after the giraffe event unintentionally casts the differences between circus suffrage and“real” suffrage in a sharp light:

“For the most part the onlookers seemed to be there to see a spectacle, to cheer or to laugh as they would at a circus parade and without any thought as to the political significance of the event for which the women had toiled so hard and to which they dedicated such earnest effort.”

Some thought the very act of riding in a parade was too unbecoming of a lady—one parade story references “society women who wouldn’t give their names”—participants too embarrassed to fully embrace their activism. After a disastrous 1913 march in Washington, D.C., that ended in violence, one anti-suffragist claimed that

“Womanhood can not have its cake and eat it too. If women want the kind of consideration to which they have been accustomed they must live by the conventional standards. When women cease to conduct themselves as ‘ladies’—when they adopt the motives and antics and methods of the circus—they must not expect delicate consideration.”

“Delicate consideration” in this case referred to not having objects thrown at your head while you express in public your desire to vote.

A suffrage parade in New York City, May 4, 1912 (photo by American Press Association, via Library of Congress)

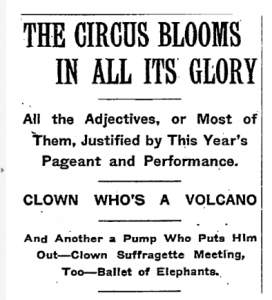

This is not to say circus employees didn’t have a sense of humor about the issue, although it seems wrong to suggest that women should have a sense of humor about being condescended to and attacked verbally and physically. The circus did, after all, lampoon current events, even issues some individual members may have had strong feelings about. In March 1911, the Times reports that one act in the Barnum & Bailey show at Madison Square featured a “clown suffragette meeting, at which one 3-yard-wide real housewife preached the gospel of the hearth to her ‘eddicated sisters,’ and preached it so long that one of the men present lost his head and went screaming away without it…” I can’t find any record of such a show after the suffrage group was formed, though.

Groups of women in different parts of the country, and, it seems, different social classes, reacted differently to the circus suffragettes. While New York City socialites shunned the circus as too flashy and attracting the wrong sort of attention and bad press, other groups embraced them. Some suffragists camps consisted of “society women who wouldn’t give their names,” but others were glad for the help and public attention afforded by circuses, even in the face of backlash. Suffragists in Ohio and Wisconsin are on record as having joined in circus parades on their way to the big top. Some suffrage groups even took cues from the circus, bringing their cause to the public sphere, and plenty of spectacle along with it.

Perhaps a lesson about political in-fighting can be found here. What would have happened if the circus and proper society had combined their physical and social strengths and acknowledged they were all fighting for the same cause? Such squabbling almost seems petty a century later, as suffrage seems like a foregone conclusion. Finally, it’s useful to remember that politics has always been a circus, and flash and spectacle can be alternately or simultaneously inappropriate and useful. But whether you do it while riding bareback, juggling torches, or just watching the show in bemusement, please go vote this election season. Miss Suffrage would have wanted you to.

Sources

Katherine H. Adams and Michael L. Keene, Women of the American Circus, 1880-1940

The Bowery Boys, “Circus Activism: Barnum’s Female Stars Demand Right to Vote, Name Baby Giraffe ‘Miss Suffrage’ at Madison Square Garden.”

Janet M. Davis, “Ladies of the Ring.”

Margaret Mary Finnegan, Selling Suffrage: Consumer Culture & Votes for Women

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.